Every PS1 Game – Syphon Filter

While playing Mission: Impossible recently, one game kept popping into my head: Syphon Filter. Even though they were produced by different teams in different countries, they’re both third person spy adventures that look and feel similar and were released at similar times. I played Mission: Impossible as part of a “Game of the Month” challenge, and it felt so rough. Did Syphon Filter, with its better reviews and my childhood memories, stand up better than Mission: Impossible? I had to find out.

It starts on a high note; the intro is just as cool as I remembered it. You start on surface streets and you’re soon in the subway surrounded by burning train cars.

I went back and forth on whether to use Widescreen Hack for this game. The actual gameplay area is basically perfect; there is no pop-in or weird glitches. The on screen UI textures are a bit stretched, which isn’t really a big deal; the radar is basically useless anyway, and your equipped weapon just looks wide.

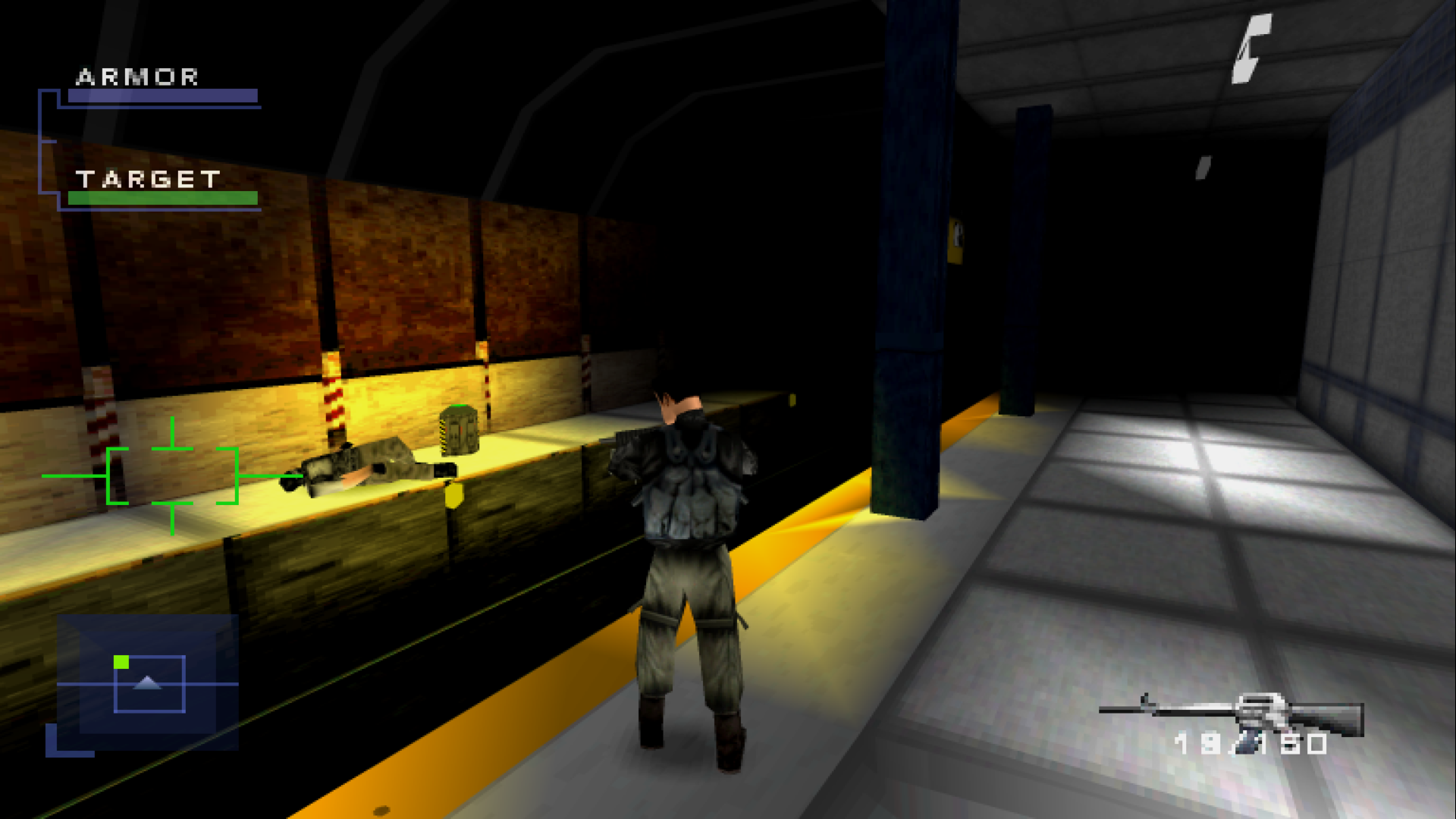

Ultimately, I decided to stick with the original 4:3 frame for this game due to one of the main features that makes this game vastly better than Mission: Impossible: the targeting reticle.

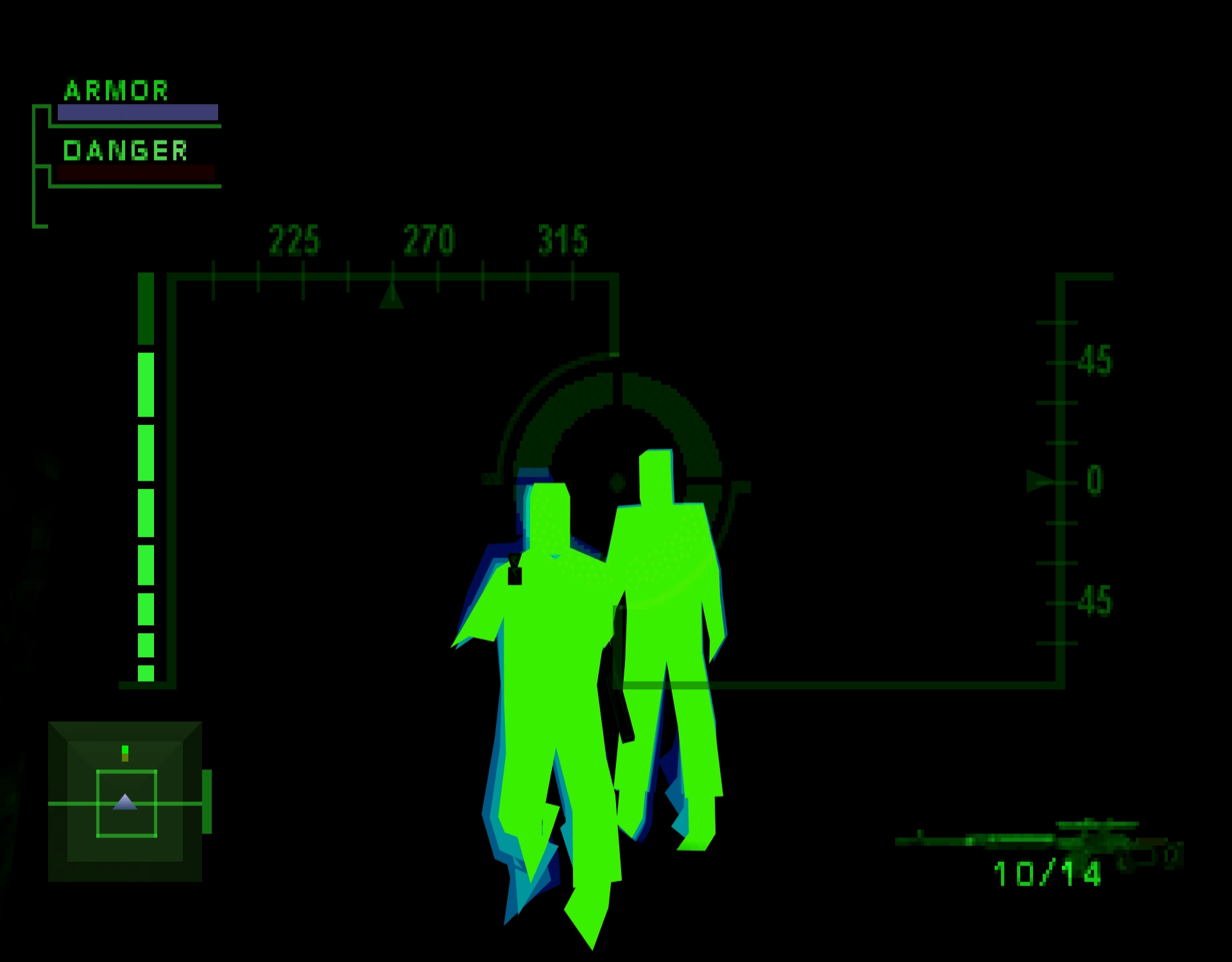

Like Mission: Impossible, Syphon Filter offers two targeting modes: R1 is an “auto-target” mode, and L1 is first person manual aiming view. This is so much slicker than Mission: Impossible, which has an auto-aim function that doesn’t tell you where you’re aiming, so it’s very difficult to not shoot innocent NPC’s when you’re trying to kill a baddie. Unfortunately, this is the main casualty of the widescreen hack and the reason why I chose to play this game without it: the further the aiming reticle is from the center of the screen, the more mis-aligned it gets. In the above screenshot, the reticle is ostensibly locked on to the enemy on screen.

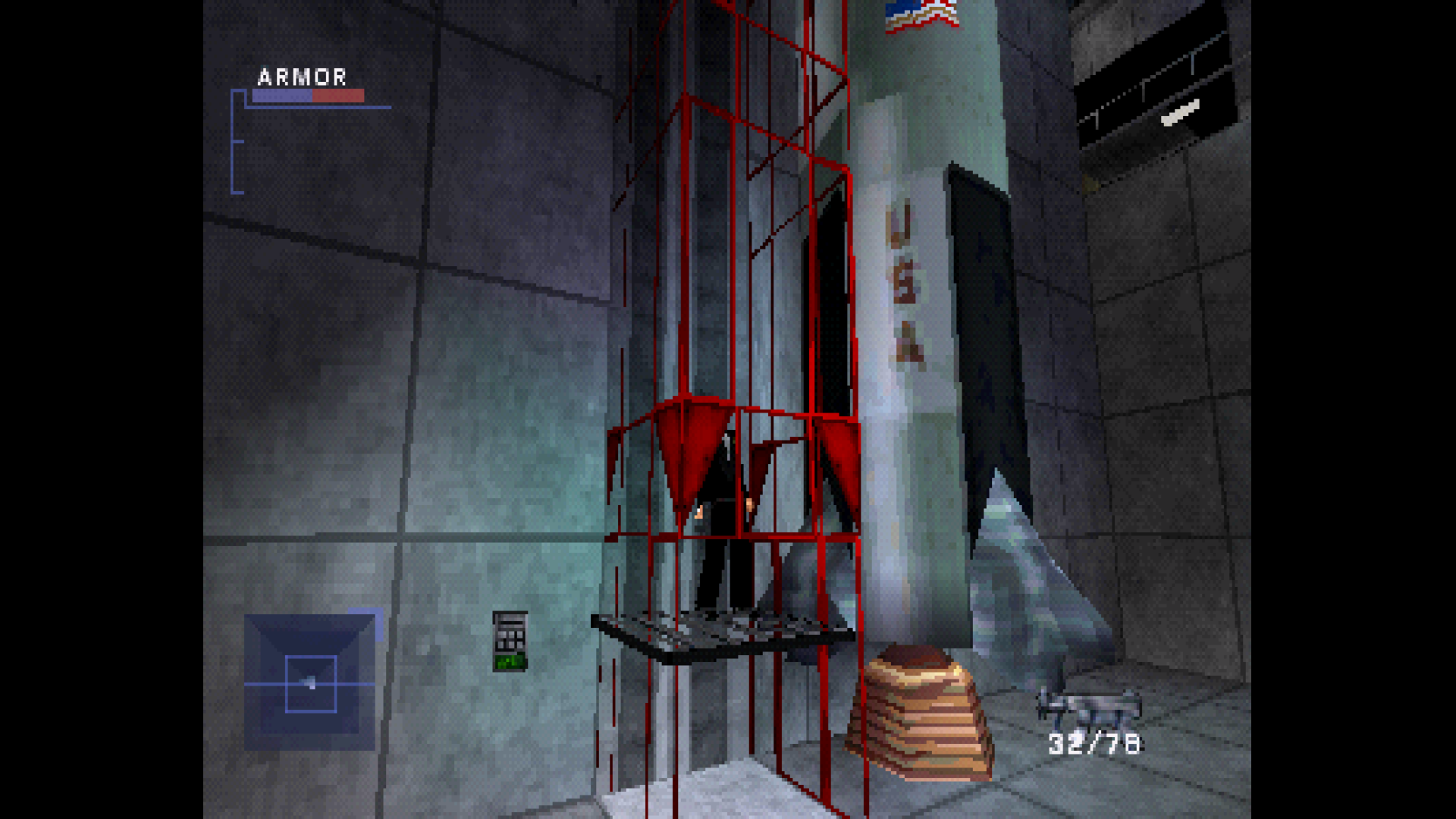

One of the gameplay mechanics in this game is climbing. You can’t jump across gaps in this one, but there are a bunch of different types of “jump up, hang, shuffle, pull yourself up” type of puzzles.

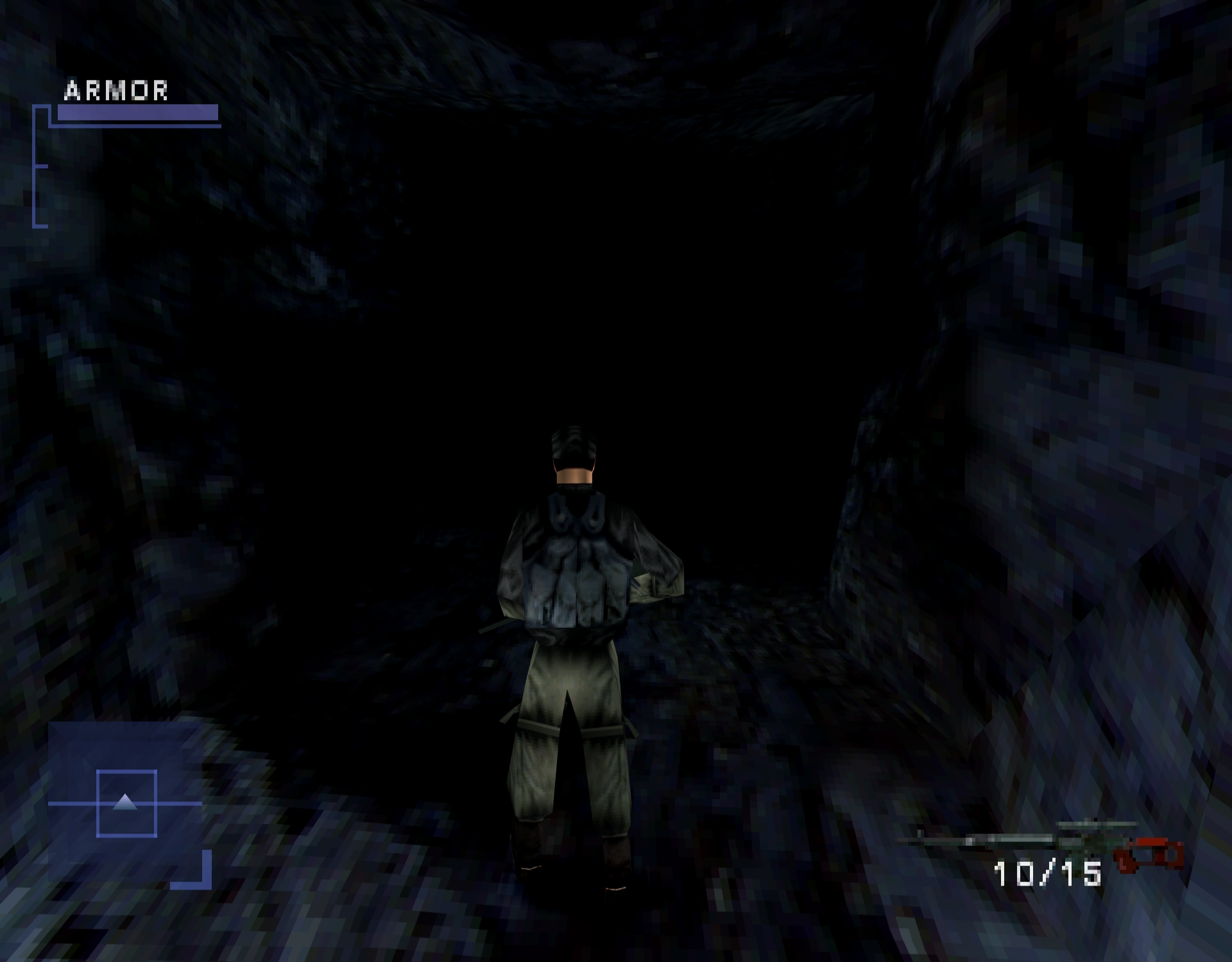

Man, I love the lighting in PS1 games.

This is an amazing demonstration of two of the coolest emulation enhancements: internal resolution and PGXP. The raised internal resolution is apparent in all the normal stuff like extra detail and reduced jaggies on the characters, but just look at that Stonehenge sign. It goes from absolutely unreadable to sharp as a tack! And you can see the effects of PGXP on the bricks on the left, which go from zig-zag to a proper straight line. Maybe I should have also done widescreen hack for the triple whammy.

I once read a comment on Discord that went something like, “I turn up the internal resolution just so I can see.” Yep, that tracks. Even at a close distance, the sign is completely unreadable at native resolution. Crank it up and it’s crystal clear.

With that said, there were a couple times where I switched to software rendering to get the original PS1 look. Check out that lovely dithering. What are those three letters? Sometimes the low resolution provides an almost watercolor look.

I didn’t really think about this until right now, but Policenauts also had a fight inside a space-related museum.

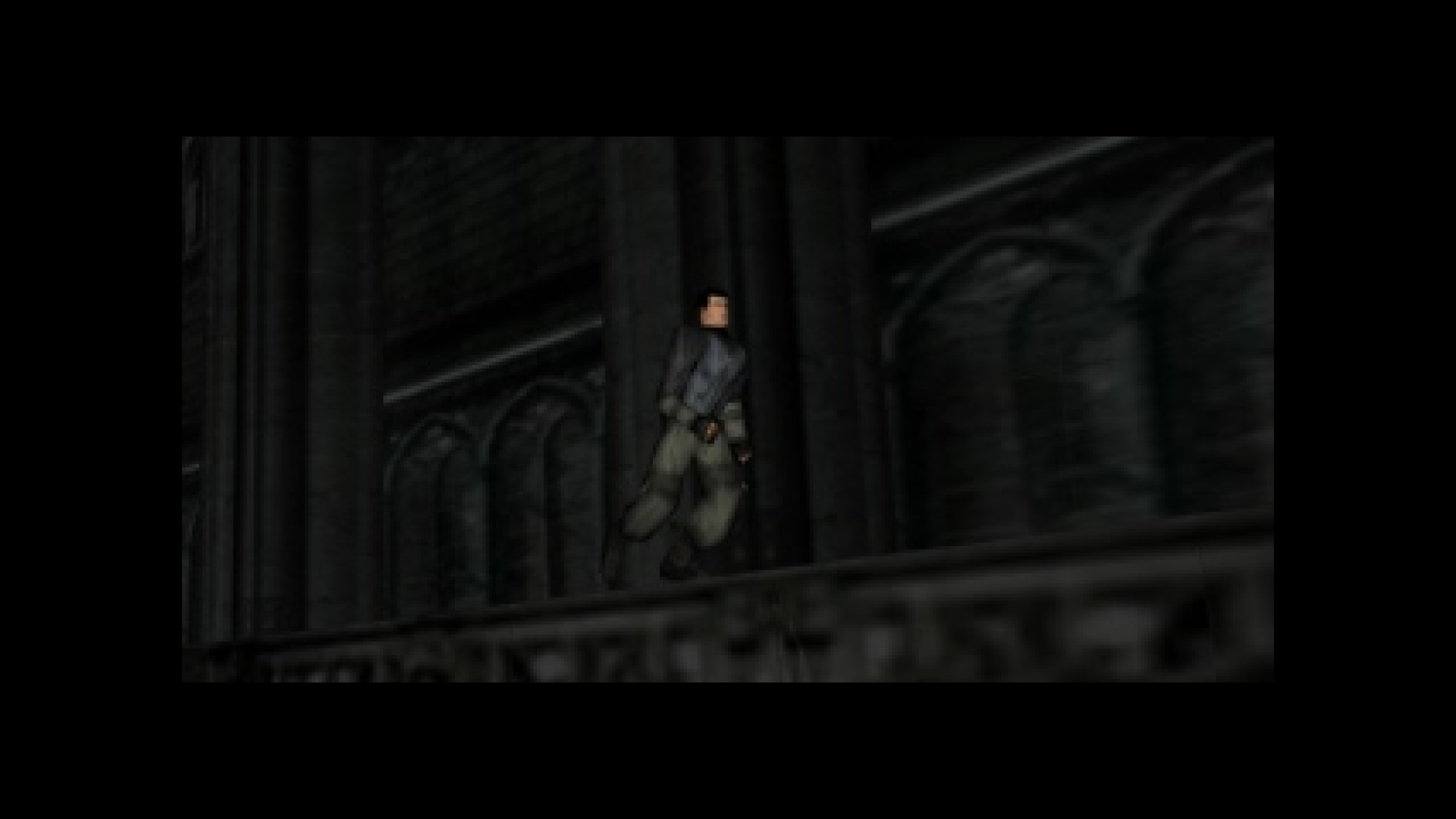

This was one of the scenes that really stuck out to me as a kid. You reach a dead end in this circular room, and there is just a catwalk spanning across. A bit of shimmying later…

Most of the cut scenes are pretty lame, just like Mission: Impossible; they look like they’re rendered with the in-game engine but the compression makes them look worse than the actual gameplay. But I always thought this was a cool scene: you fall through this skylight and the glass shattering is the epitome of 90’s CGI. It looks pretty crappy by today’s standards but when I see this effect I’m 12 years old again.

Aw yeah, gotta have a T-Rex in there. Coming soon to this website are two of my favorite games: Dino Crisis 1 and 2.

With the simplicity of the models and low encoding bitrate, the cutscenes looks even worse as a screenshot.

I think that’s the case for a lot of PS1 games; a simple screenshot rarely does the FMV’s justice. In motion, by 1999 standards, this particular scene was actually pretty rad.

Maybe I’m a little too focused on cars and motorsports, because my first thought was “Chevron??”. Actually, that white-blue-red tricolor flag has belonged to the Russian Federation since 1991.

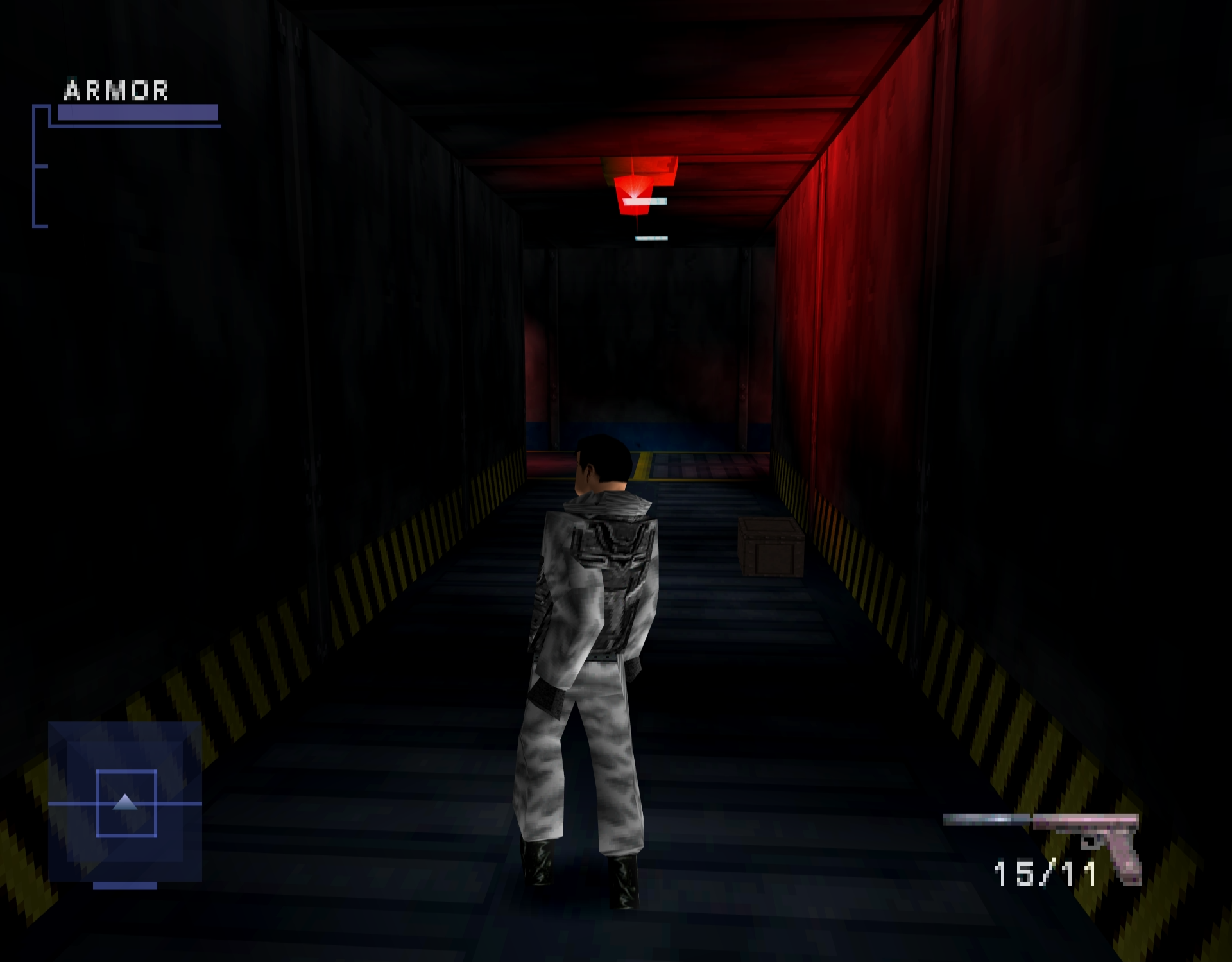

Another cool bit of simple 90’s lighting; check out the effect of the rotating light. It even affects the color of Gabe’s uniform.

They do give you a map with your location on it, but it’s borderline useless. It’s hard to tell apart the positive and negative spaces, and often what looks like a wall on the map isn’t one in the game–and vice versa.

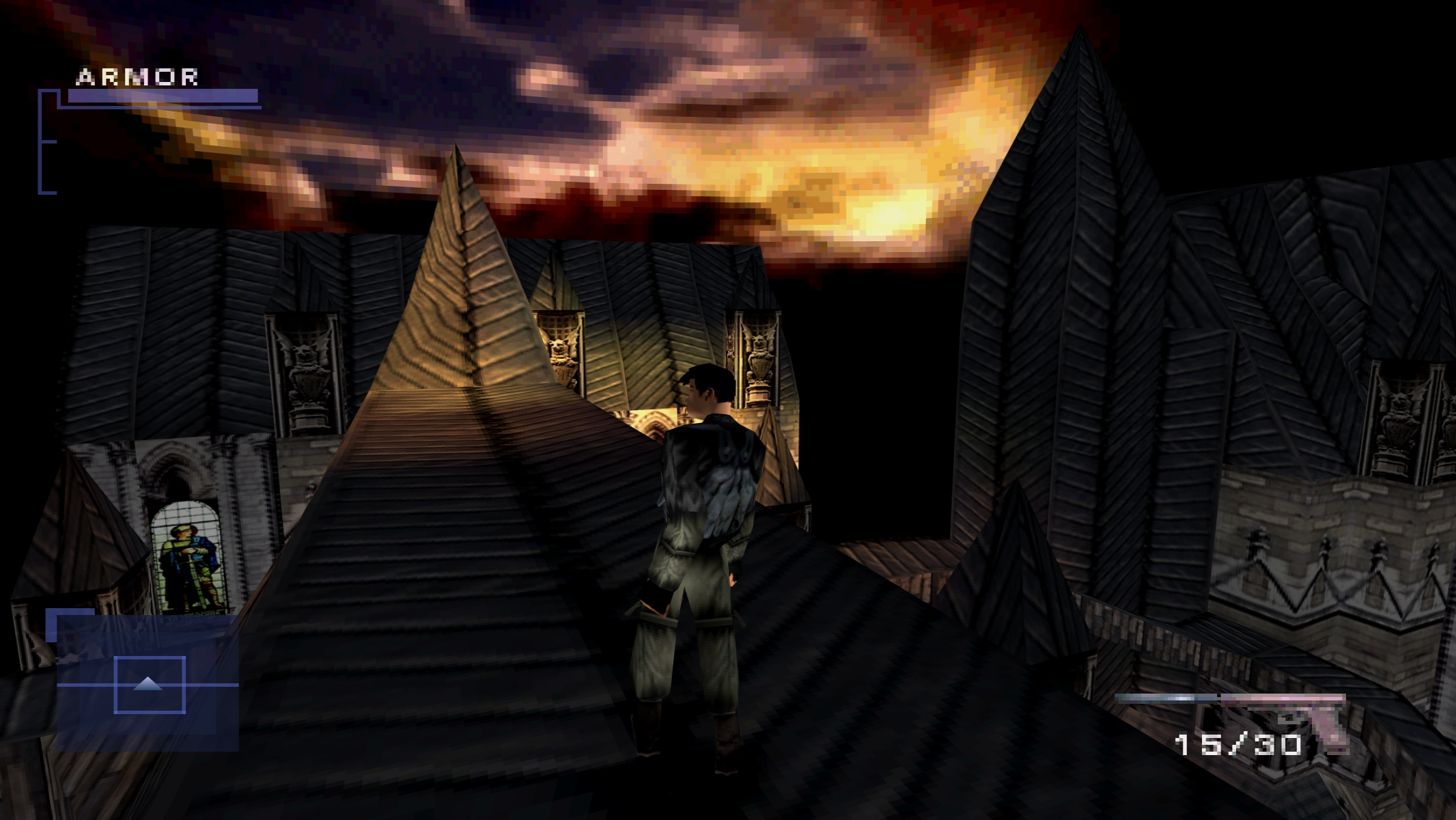

Graphically, this is my favorite scene of the game. The one above is the native 4:3 frame…

…and here’s a similar spot in widescreen, just because I like it.

Some of the architecture makes no sense, like that big flying bridge at a strange angle. But it facilitates the gameplay, so I give it a pass.

You get a neat aiming view with the sniper rifle. None of the numbers or text mean anything, but they just add to the atmosphere.

This game came out a few months after Tomb Raider III and rivaled its graphics.

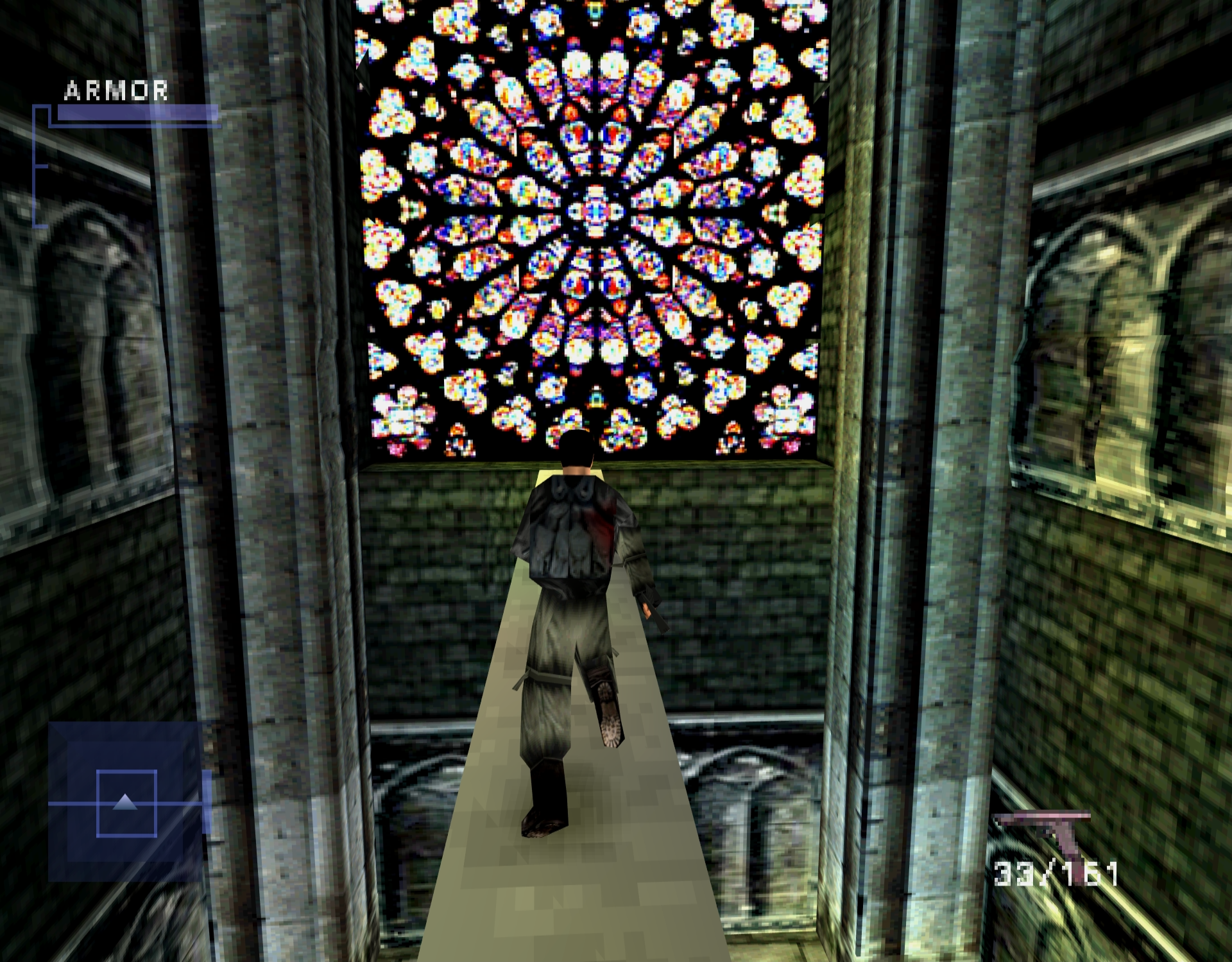

More nonsense architecture. But if you remember what happened to that big glass pane when we dropped down into it…how could we not run straight toward this one?

Here we go!

Aw yeah look at that shattering glass! Party like it’s 1999!

It turns out–no surprise–that Lian Xing is actually a badass! Let’s follow her outta here.

There are many elements of PS1 games that have aged very well. Cutscenes like this? I love them precisely because they’ve aged so poorly. And the voice acting is even worse. It’s intriguing, in the way that The Room is intriguing.

At one point you get a scanner that’s supposed to help you find particular items, but it doubles as a sort of X-ray vision to see where the enemies are through walls.

In the L1 manual aiming mode, you always get this feedback when you’re aiming at a head. Unfortunately, the aiming is slow and laggy, like using a paint stick to stir a bucket of mud.

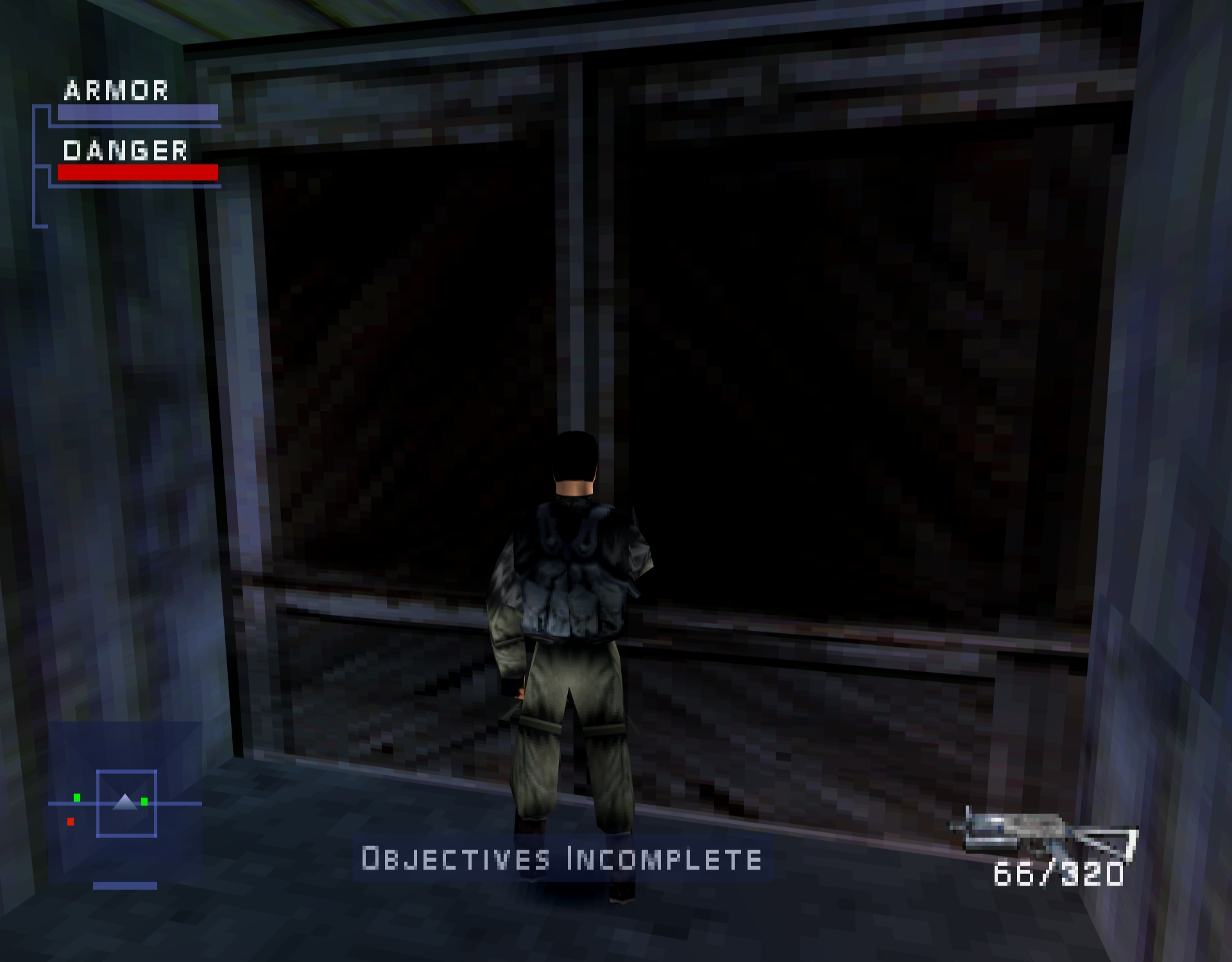

Among the many frustrating elements of this game is the confusing level design; from the beginning it’s often unclear where to go next, and in later levels you can find yourself fighting to a certain point which turns out to be the end of the level–but you haven’t completed your objectives, so you have to double back and finish them, then return here when you’re done.

There are so many textures in this game that are much higher resolution that you can ever see on an original console; it’s really cool to play on an emulator and see things that have been hidden for years.

There were some dark places before, but now we’re underground. Oh yeah, we did have a flashlight…

What the hell. This is ridiculous. This area makes Silent Hill look like Katamari Damacy.

You get a night vision sniper rifle, but you can’t look through the scope and walk. So you have to take a few steps, check the scope, and repeat.

The amazing flashlight that only lights up faraway item boxes and the ground within 3 feet.

The final boss battle is just ridiculous. I’m still reluctant to post end-game spoilers even though the game is 25 years old, so I won’t spoil the battle, but I will point out there is only one specific way to beat this scripted boss fight.

Helicopter’s here, everything is okay now.

Or is it?!? Syphon Filter 2 was released thirteen months later, in March 2000, and is a direct sequel which takes place directly after cliffhanger ending of this game.

Syphon Filter is such a mixed bag. The levels are really interesting, but it’s often hard to figure out where to go next. The overall story has a good concept but the story beats out are laid out in a confusing way that made it hard for me to engage with the plot. The auto-lock aiming is ahead of its time, but most enemies have body armor which means you have to head shot them using the molasses manual aiming. And so it goes: this is a very ambitious game that has dated very poorly.

Back in 1999, it was easy to overlook these flaws because that was the state of gaming. This game was generally very well reviewed, as many of the aspects that seem dated now were still fresh at the time. It was nice to re-play this game after Mission: Impossible because it reminded me of that perspective. Syphon Filter has lost much of its luster over the years. It now serves as a signpost of an era that we’ve long since moved past, a sort of “we were here” marker that gives us perspective on how far we’ve come.

Pingback: Every PS1 game – Syphon Filter 2 | Star Road